Then I went further and investigated the history of the word. “Science” derives from the Latin word “scire” which means “to know or understand.” And in fact, the approach taken by Waldorf Education is to support children in getting to know the world, and then to help them understand it.

How exactly can one describe the Waldorf approach to teaching science? Here’s a starter list.

First, of greatest importance is that the science curriculum is presented in a way that meets the developmental stage of the child. As some of you probably know, the Waldorf curriculum is keyed to a particular view of child development. Every stage of a child’s life is seen as embodying a certain way of experiencing the world, and the curriculum for that stage is keyed to that experience.

Secondly, we start our study of every subject with what is closest to the child, what the child knows best—the human being. We focus on the connection between the human being and the world, which supports both a deeper understanding of oneself as a human being and of one’s responsibility to the natural world.

Third, our understanding and presentation of science are based in observation and experience. This knowledge is transmitted in imaginative stories to children through second grade. From third grade on, however, Steiner sees children as “delving into the elements of their immediate surroundings that they are capable of understanding.”

And fourth, whatever we teach will be artistically presented. Certainly, every Waldorf teacher is not a trained artist, and it would be unrealistic and unfair to expect that. But every Waldorf teacher must be seen as striving to present material as artistically as they can, and indeed, working hard to improve their skill. In Steiner’s lectures, science through the Third Grade is called “the Study of Home Surroundings.” Grades 3-6 focus on what he calls “Nature Studies.” Grades 6-12 refer to the specific disciplines of physics, chemistry, and so forth.

Early Childhood

Young children relate to the world through their senses: sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste are the obvious ones. Young children do not analyze, nor do they even necessarily verbalize, their experiences, they just actively engage with their environments. Watch a child on a playground as she climbs onto a playhouse roof, adds water to sand, looks up at the sound of a dove, digs up the grass to uncover—and collect—an earthworm. Here we have obvious demonstrations of physics, chemistry, botany, and zoology. Early childhood in a Waldorf preschool program establishes the foundation for later, more formal, explorations in science. Teachers provide the possibilities of experience for their children.

Every week, for example, the class goes on a nature walk. The point of the walk is: the walk itself. There’s no goal, but the children are encouraged to look around, to listen, perhaps to smell or to touch. Cooking is an integral part of the early childhood program, and cooking involves touch, seeing, taste, smell, and listening to instructions, or perhaps to an alarm that indicates the food is ready to eat. Fundamentally, cooking is chemistry. When substances are mixed together, when heat or cold are applied, the substances are changed. (We are pleased to offer cooking classes this year for all grades at Lotus & Ivy!)

Each week includes time for modeling with beeswax or clay—a direct experience with manipulating matter. Painting provides experiences with light, water, and color. And of course, clean-up time means organizing the room and creating order out of chaos. Scientists must know how to organize and systematize their questions and their observations. Through all these activities, experience is the key, not intellectual or fact-filled discussion. If a child asks a question, the teacher will respond in simple, straightforward, and literal language. Sometimes the teacher will respond with another question because the teacher knows that sometimes questions are more valuable than answers.

First and Second Grades

As the child moves into Grade School, experience is still primary because this is the way children of this age relate to their surroundings. Now, the children have a responsibility in caring for their world. They take turns watering the plants, washing the paint jars, sweeping the floor. Often the teacher in these early grades continues the practice of a nature walk as well as cooking with the class. The children continue to paint and model and of course, to clean up. They become fierce classroom helpers.

Again, intellectual discussion about what they’re doing does not enter into the activity. They are experiencing how their work transforms the environment and how necessary human action is to supporting life in the natural world. Is this plant unhappy? Is it getting too much water, or not enough sun? Here are questions, based on observation, which help lay a foundation for later scientific inquiry.

Now, stories begin to reflect activity in the natural world. The children hear about the change of seasons, the division of day and night, what happens to a seed underground and what happens to a squirrel in the treetops. All of these themes, and many others, are addressed but in a story form. At this age, children live in a rich, imaginative world.

Here is an example from a phonics lesson in first grade. The children write the letter and talk about the sound we say when we see it. They then think of words that start with that sound, and we draw a picture of the word. Often the words are the names of animals. As we draw, we talk about where the animal lives, what it eats, how it moves. In one second grade story, we talk about Peacemaker who took the message of peace to the people in his stone canoe. A stone canoe? Wouldn’t it sink? St. Brendan explored the North Atlantic. What hardships did he overcome? The donkey sat down in the middle of the stream and wouldn’t move; its owner filled the bags with sponges. What happened when the salt got wet? What happened when the sponges got wet?

Teaching through stories matches the learning style of the child at this stage. The stories are always based in reality, so that by including facts about the natural world—the animals and plants children are familiar with or are interested in—teachers are presenting information that children will remember more easily than if it is presented in a more straight-forward manner. The material addressed in stories will return in later school years as lessons in geography, botany, zoology, and the other sciences. In emphasizing connections and sequences of events, stories help to lay the foundation for scientific thinking.

Third Grade

Waldorf Education recognizes and respects the changes which often occur in children around the age of nine. At this point, many children experience a sort of existential crisis, as acknowledged in many biographies. At some level, the child understands that a holistic connection to the world has been lost and the child can feel very alone.

On the one hand, children of this age can sense the greater freedom of adolescence and adulthood approaching them and are excited by it. On the other hand, they realize at some level that they are not capable of complete independence, so they can feel a deep insecurity and anxiety.

Waldorf Education supports third grade children by giving them a curriculum that emphasizes how people came to live on the earth—how people grew from an innocent age when everything was given to them or made for them, to a point when they could create what they needed.

An understanding of measurement is crucial for human activity. I started this block after telling the story of Noah. This allowed us to think about the fact that how we measure has changed through time. We went outside and measured the dimensions of the ark on the playground. It was so huge, it was almost unimaginable. Then we looked at the later practice of using the human body to create units of measurement. We each create our own “feet” and “inches” and use them to measure furniture and the classroom itself.

This curriculum includes studies of shelter construction throughout history. This study culminates in a building project for the class. Projects I’ve seen include an outdoor oven for baking bread, a wall, a greenhouse, and a yurt. The emphasis is on creating a structure that the school can use. It’s very helpful for children in the third grade to learn about how homes are built—the planning, the machinery, the materials used. My parents built a house when I was young, so I used that experience to teach them how many people work together to create a home.

The children study traditional ways of making fabric. So they might clean and card sheep’s wool and spin it into fiber that they weave into a scarf. They’ll meet fiber craftsmen and learn about working with large looms.

One block will focus on the development of agriculture, and the children will study the seven grains that have supported human life throughout history, and in different climates. They’ll work in the school garden or perhaps create their own, learning how and why we compost. They’ll bake bread, make soup, or chop vegetables for a salad. My mother’s family were farmers; so, again, I used my own story to illustrate this study of agriculture.

Measurement will be extended to include weight, volume, time, and money. I told the class about my family’s small store; we talked about the prices of the items sold there and how much things have changed. It’s always good for the children to hear a teacher’s own life experiences, as it strengthens the bond between the class and the teacher.

By the end of the third grade, the children will feel that they have gained a competency in creating shelters and clothing and in growing food, as well as confidence in their own capacities. And of course notes on animal husbandry will be explored when relevant. Some fortunate Waldorf schools partner with a farm or raise chickens or goats, or tend bees. In the Third Grade curriculum, we see the foundations for studying architecture, botany, zoology, the physics of weather systems, the importance of geography in the development of culture.

Fourth Grade

By fourth grade, the children have already learned much about the cycles of the day and the year, and plant and animal life. Their learning has not been sentimental or fictional, but rather based on observable elements in the natural world.

The fourth grade, however, marks the first time that a science is explored as a separate topic. We begin with studying animals, but we enter into this study through a contemplation of the human being. In the first zoology block, we consider the human form.

What do we notice about the human being? The human head is round and hard on the outside and soft on the inside. It moves very little; in fact, it is very like royalty being carried about in a carriage. The head carries our eyes, ears, noses, mouths, and brains. What happens in my head? I connect with the world through those senses, and I think. Our limbs are long and thin, hard on the inside but covered with soft tissue on the outside. In contrast to the head, the limbs are very mobile. With my limbs, I reach out into the world, I walk, I create. I act.

The human hand is a true miracle. Think of what you can do with your hands: gesture, write, model, paint, touch.

In between the head and the limbs is the chest. The form of the chest area is also in between the forms of head and the limbs. At the upper end of the chest, the ribs connect, forming a sort of open sphere. The lower ribs are not connected across the chest and are straighter, like the limbs. We think in our heads; we do with our limbs. What human function takes place in the chest? This is where we experience the rhythms of breathing and heartbeat. This is where we feel. We know this because of the obvious relationship between breathing, heart, and strong emotions. When angry, blood might rush to the face while breathing speeds up. When threatened, blood might rush to the feet and breathing slow down.

Discussing the form and function of these three aspects of the human being introduces the child, in a pictorial and gentle way, to human physiology. The next step is to relate this material to animals.

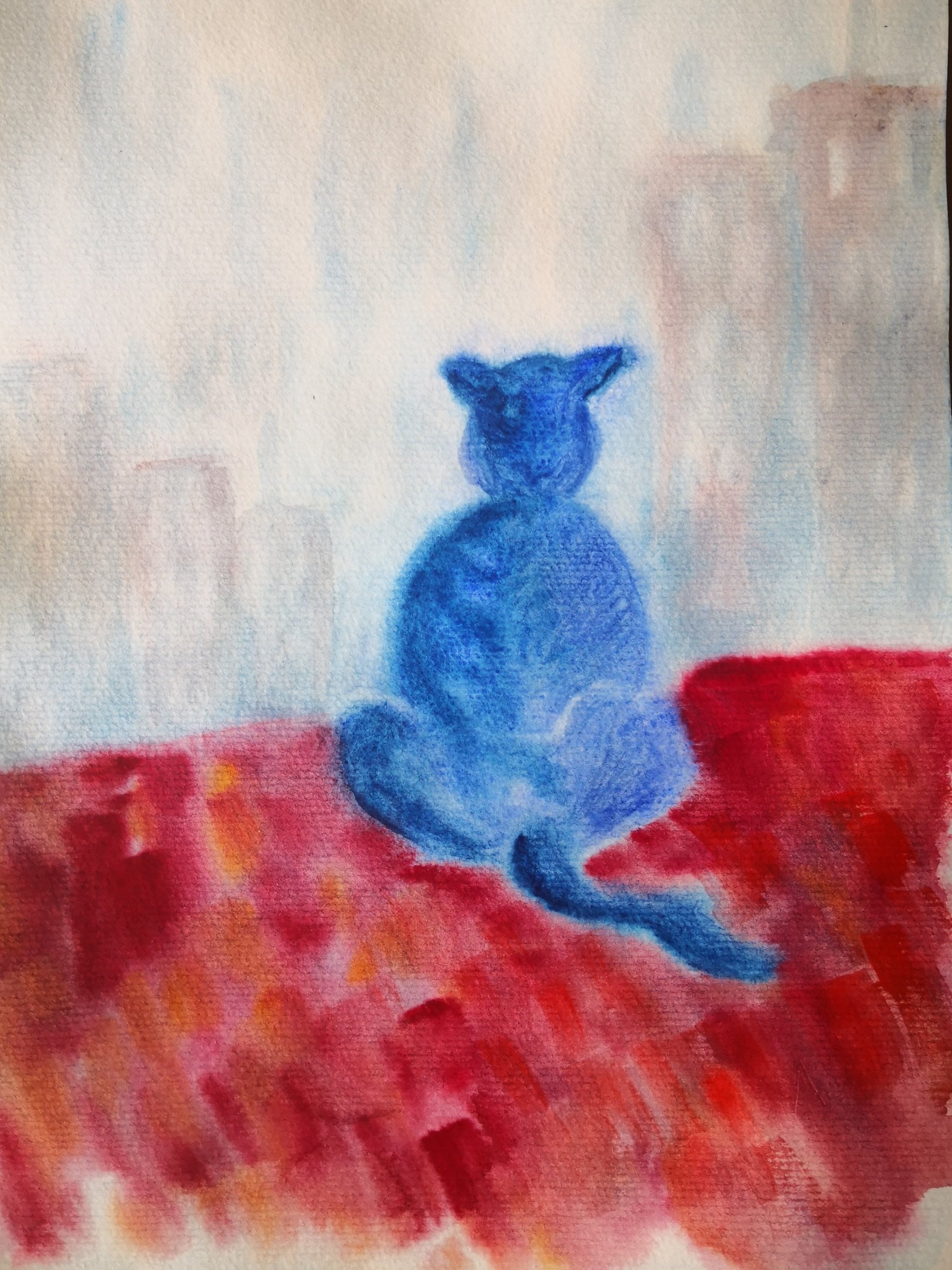

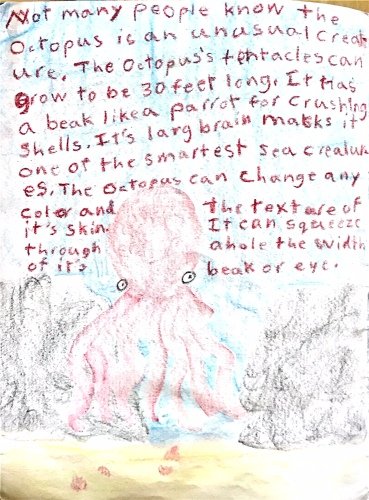

Are there animals which embody the head form of the human being? Yes: if one examines the octopus, squid, or cuttlefish, one sees an animal which appears to be mostly head. The teacher chooses an animal to start with and presents as full a picture as possible of where and how that animal lives. The goal is to present such a rich imagination of the animal that the children experience it as being a “head” animal.

Are there animals which represent the chest form? The little mouse is almost all chest, with a tiny head and miniature limbs. Where and how do mice live? What do they eat? How do they move? Have you ever seen a mouse? How did the mouse act? And what about the limb form? Here we can study the horse and admire the gracefulness of its movement and how it relates to its environment.

The second animal study of the fourth grade focuses on three animals—the eagle, the lion, and the cow—as representations of the three primary physiological systems of the human body. The eagle, with its keen sight and focused flight, represents the nerve/sense system. The lion, with its great heart, represents the rhythmic system. And the cow, with four stomachs and day-long grazing, represents the metabolic/limb system.

But wait. We can all understand the comparison between the thinking of the human being and that of the eagle, as well as the comparison between the heart/lung systems of the human and the lion. But what about the action of the limbs? The human being cannot run like a wolf, leap like a deer, swim like a fish, or fly like an eagle. Comparing the limbs of the human being to those of an animal, we can see that animals far surpass humans in specific capacities. We realize that, rather than perfecting one type of motion or skill, in the human limb system, the human being is a generalist. The entire animal kingdom can be seen as present and in harmony in the human being. It has seemed to me that every fourth grade class has children who love animals and who see humans as being equal to animals. These children rage at the disrespectful treatment of animals, and rightfully so. But Waldorf Education teaches that there are four kingdoms: mineral, plant, animal, and human. How do we bring this to children? What does separate humans from animals? I once brought part of my class to understand that humans have choices and animals don’t—an animal acts pretty much like others of its species do. A cat is a cat, a dog is a dog. But each human is unique, and one reason that is true is that human beings have choices.

Still, at least one child did not accept this and confronted me with, “Well, what if you wanted to be a professional football player? You wouldn’t have that choice!” [This was a child of another Waldorf teacher!] It was a classic “gotcha’!” moment. My response was, “I couldn’t choose to be a professional football player, but I could choose how I would deal with not having that choice. Would I stomp up to my room and cry at the unfairness of it all?” This response brought the entire class to a thoughtful recognition of their own choices and their own privilege as human beings.

The fourth grade also extends the “geography” study. In third grade we studied our immediate surroundings, drawing maps of the classroom and our rooms at home. In fourth grade, we draw floorpans of the school itself and the routes taken to get to school. Finally, we draw a map of our state. Throughout this block, we are learning about the differences in soil, landforms, and water availability in the various areas.

Fifth Grade

Now we come to the fifth grade. As I stated earlier, Waldorf educators see the natural world as being composed of four kingdoms: the mineral, the plant, the animal, and the human. As we move into formal presentations of science, we start with that which is closest to the human child: the animal kingdom. This allows the child a gentle transition from self to world, as most children love animals and, at the same time, can be a little objective about their relationships to animals. In fifth grade, we study the plant kingdom—one more step removed from the human being. In sixth grade, we’ll study the mineral kingdom, which is as different from humans as one can imagine. Twelve-year olds, who are trying to work with the newfound awkwardness of their own bodies and emotions, thus learn about the inside of the earth—the “emotions,” if you will, of the volcano and the earthquake. The earth itself is not finished yet! On some level, that has to be reassuring to a middle school child.

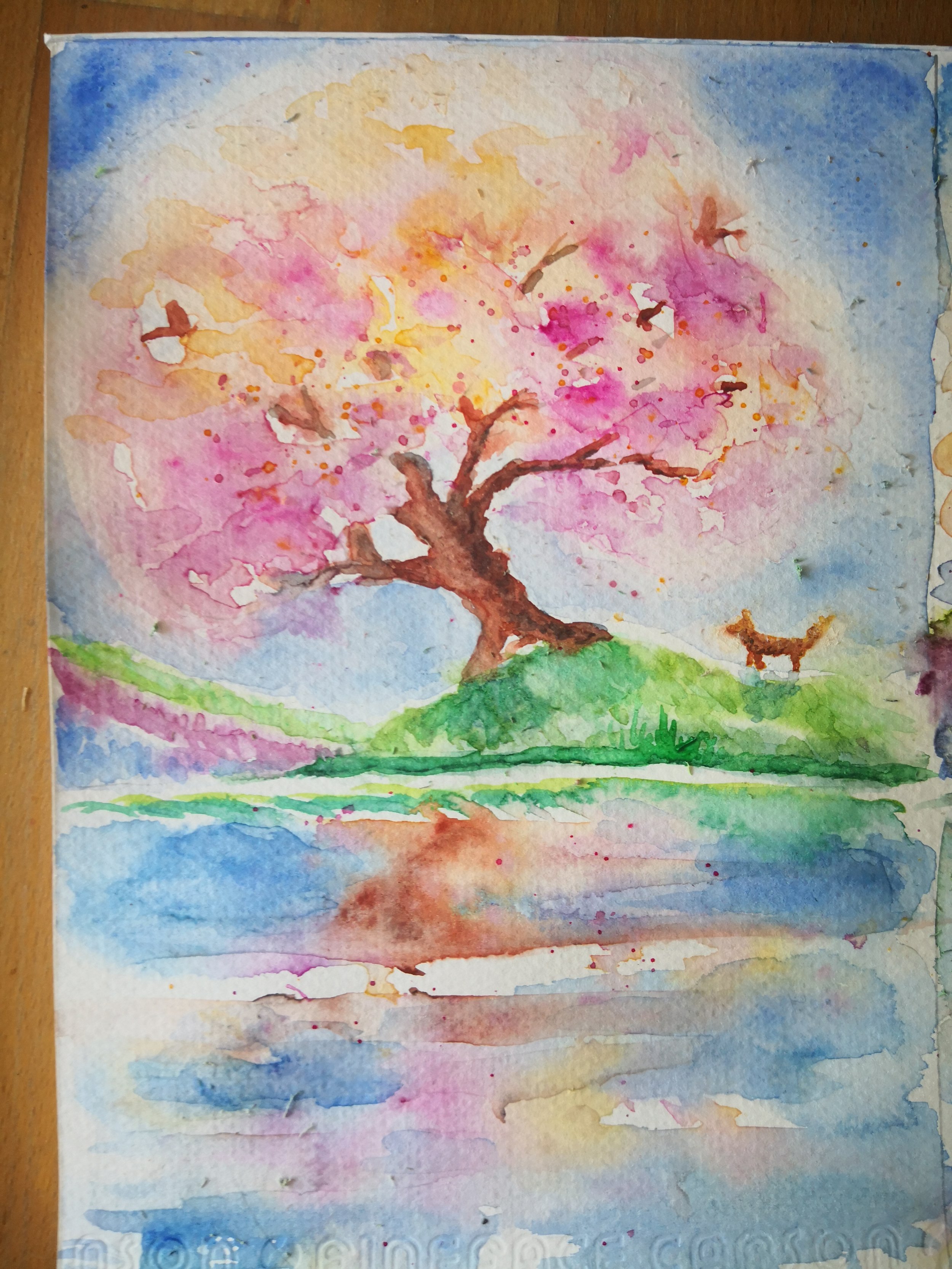

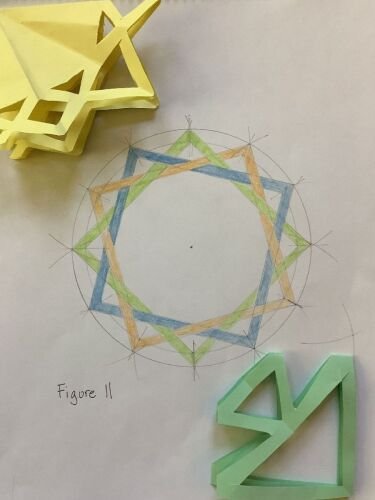

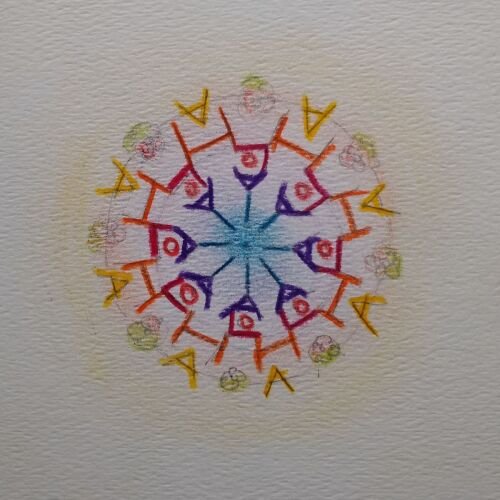

Here we show an example of an archetypal plant. It has roots, a stem, leaves, and a blossom that contains little fruits and seeds. We study each part of the plant in isolation; and we talk about what the plant needs to flourish. We study the life cycle of the plant, illustrated through the cycle of the seasons. We go a little deeper into the form of the flower and notice that each flower presents a geometric shape in the arrangement of its leaves.

Next, we compare the human being to the plant. What part of the plant most resembles the head in its lack of movement and in its sensitivity to its environment? The root. What part of the plant most resembles the metabolism in its work with heat and transformation? The blossom. What part of the plant most resembles the heart and lungs in the delivery of essential nutrients to the roots and blossoms? The stem. Especially in the grade school, we connect the human being to whatever we are studying. While this can seem egocentric and/or anthropomorphic, the effect is in fact the opposite. The children learn that we are all connected to each other and to the world; they learn a deep respect for their environment and a responsibility toward it. As George Washington Carver remarked, ““When I touch that flower, I am not merely touching that flower. I am touching infinity.”

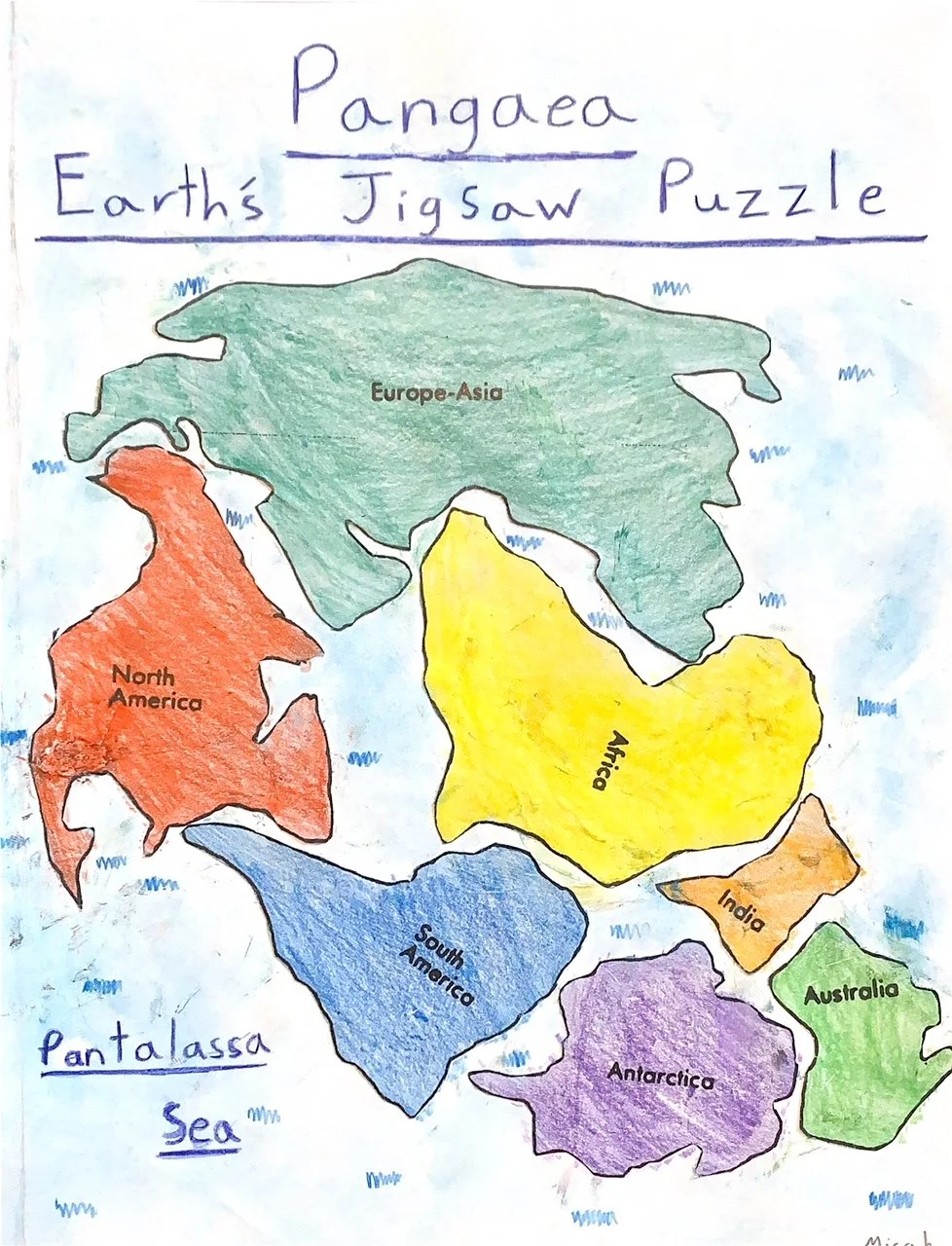

Now we study certain plants in more detail. By this time, the children are creating their own compositions from the conversations we’ve had in class. We think of the plant kingdom as being a “ladder,” progressing from the “root” plants [fungus, algae, lichen], through the “stem” plants [mosses, ferns, conifers], to the flowering plants. The flowering plants include the grasses and culminate in the rose family. Finally, we compare the growing plant to the surface of the earth itself. In the illustration, if you imagine the earth on its side with the polar region to the left and the equator to the right, you will see how this works. Plants closer to the polar regions are primarily root, and as we come closer to the equator, the entire six-part plant appears: root, stem, leaf, blossom, fruit, and seed. Moreover, the closer we come to the equator, the taller plants become. This analogy also works when we look at the landforms of the earth. High mountain regions resemble the poles; flat ground resembles the equator. And as we ascend the mountain, aspects of the archetypal plant recede until we have first roots and then no growing thing at all.

As we study the geography of North America, the students go deeper into our work with shelters in the third grade. We look at each region of the continent, not only in terms of the traditional shelters of the native peoples, but also in terms of the plant and animal life found there. The more we learn about geography, the more we realize that it is not only the foundation of human history; it also sets the stage for further exploration of the sciences in the middle school.

Aristotle once said that knowledge begins in wonder. In the Waldorf school science curriculum, we seek to respect the wonder and the imagination that children bring with them when they enter earthly life. Then we hope to help them transform their wonder into knowledge. - To quote George Washington Carver again, “Anything will give up its secrets if you love it enough.”